Can Faith and Science Coexist?

By Emily Rust

Do everyday phenomena occur because of science or is it an act of God? Jesuit scientists and those who teach at Jesuit institutions would argue it’s a mixture of both.

Take the big bang theory, says Guy Savastano, a science teacher at Saint Ignatius High School in Cleveland. “Physics tells us all of the things that happened after that event,” Savastano says. “I say, what is the prime mover?”

To have faith doesn’t mean you are contradicting science, Savastano says. “I fully think they go hand in hand. I don’t think that science means you can’t believe in God.”

Across the Midwest Province, there are countless science educators who incorporate Jesuit teachings and faith into their lessons. Bringing Jesuit charisms into a science classroom may not be as intuitive as it would be in the humanities, but these Jesuit institutions’ science educators say to work in science is to see God’s creation.

“For this to all have just happened from a big bang, I don’t think so,” says Joan Lappe, Ph.D., RN, FAAN, who is the Criss Beirne Endowed Chair in Nursing at Creighton University. “There was some supreme intelligence involved in creating everything we have and everything we are.”

Xavier University chemistry professor Supaporn Kradtap Hartwell, Ph.D.

Lappe, a researcher in osteoporosis and nursing professor, sees God’s wisdom in the nature of human physiology and his care in nursing. In her teaching, the charism of cura personalis is paramount.

“As nurses, we tend to take care of everybody. We care about them personally,” Lappe says, noting that cura personalis is one of the ways a Jesuit university like Creighton differentiates itself from lay institutions.

Xavier University chemistry professor Supaporn Kradtap Hartwell, Ph.D., sees cura personalis in another area of her profession— working and researching with students.

“It’s about building relationships with students and knowing them individually,” Kradtap Hartwell says. “Knowing which student in your class has a certain problem and giving them appropriate guidance.” She further builds upon this relationship by aligning student capstone projects with their individual career interests which improves student engagement.

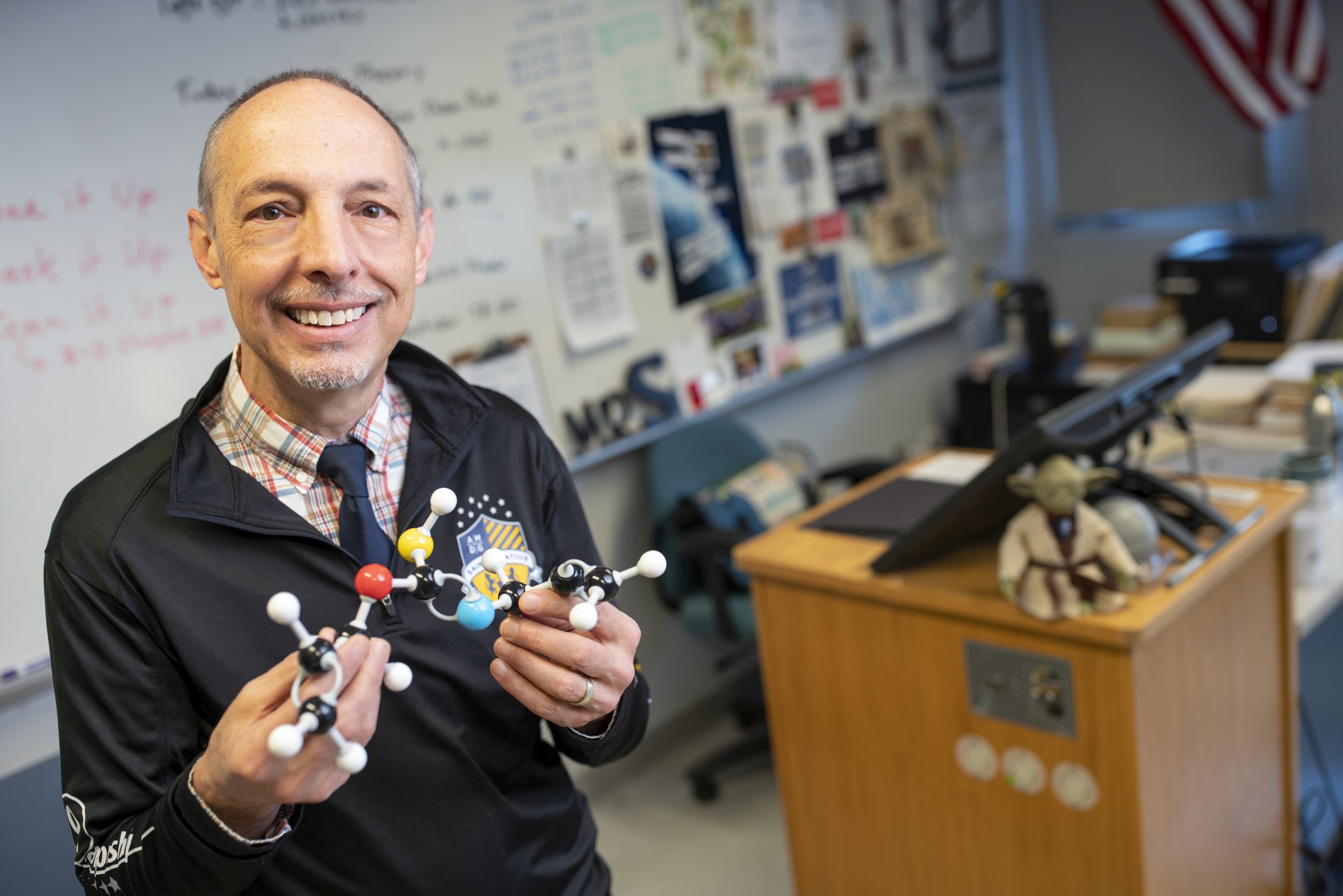

Guy Savastano, science teacher at Saint Ignatius High School in Cleveland

In Kradtap Hartwell’s lab, green analytical chemistry is emphasized to promote environmental safety. “We try to make use of safe and low cost natural-based substances instead of toxic reagents to do chemical analysis,” she says. “This is our way to protect our common home.”

Savastano has found that a similar juxtaposition between science and caring for our common home lies within Catholic social teaching and science classes.

Take coal mining, something that’s “awful for the environment,” Savastano says, “But what about the dignity and rights of the worker? It’s nuanced.”

A large part of Savastano’s teaching method is engaging students in discussions regarding ethical and societal issues and how that fits in with Catholic social teaching.

As a professor at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, Fr. Peter Breslin, SJ, often focuses discussion on the ethical issues of underserved populations. He notes that it’s part of the Universal Apostolic Preferences to serve those on the margins and encourages his students to incorporate a “missionary zeal” in their care.

“A lot of times, it’s a matter of putting students onto the critical connection and important responsibility that we as health care providers have to pay special attention to patients that don’t have access to health care,” Fr. Breslin says.

As a scientist, Fr. Breslin has an understanding of the way God created all life on Earth. “When we’re doing science, we’re in a very privileged position to be led by the hand of God to understand at a deeper level the mystery and beauty of the universe and everything in it,” Fr. Breslin says.

Emily Rust is a writer based in Omaha. She holds an MBA from Creighton University and a bachelor of journalism degree from the University of Nebraska- Lincoln.

He says that science is looking at the way God chose to create the universe.

“It’s clear to me that God chose to have life evolve. God is still creating,” Fr. Breslin says. “Every time something changes, I believe that is a choice of God. I think it’s exciting to think there’s parts of this universe that God hasn’t created yet.”

Lappe echoes Fr. Breslin’s excitement of God’s creation. “When you see the amazing things that nature has in human physiology . . . health and disease, activity . . . it’s just so fascinating,” she says. “You have to believe there is a supreme being.”

Father Breslin believes there isn’t a dichotomy between science and faith as the entire universe is God’s creation. And scientists have a special understanding of how it all works. “It’s a privileged insight to be able to understand at very structural levels how God has chosen to create,” he says. “When you understand the function of a DNA molecule . . . that it was God’s idea.”

Though Fr. Breslin notes that it’s not just scientists who have a special privilege. As humans, God has chosen us as cocreators.

“We’re participants in creation,” Fr. Breslin says. “God gives us a free hand to interact with our environment.”

The universe may have started with a big bang, but God’s creation continues to evolve each day.